Why was the 1918 flu pandemic more frightening than COVID-19?

According to the CDC, as of September 10, 2021, 652,480 Americans had died of COVID-19. This is nearly as many as the perhaps 675,000 Americans who died in the 1918 flu pandemic. But there seems to be much less fear of COVID-19 now than there was of the influenza pandemic then, at least in some parts of the United States. Why?

Of course, the first point to make is that there was certainly denial and minimizing in the United States in 1918, which people used to justify holding everything from war-bond rallies to weddings. Still, after the terrible month of November 1918 this declined. Is the difference between then and now in part that we live in social media bubbles? I think that there is some truth to this, but there are a few factors that explain the different attitude that many people had towards influenza then.

In 1918, there was a “W” shaped mortality curve, as most people who died were infants, young adults and the elderly. Before the arrival of the delta variant, there was a perception that those people most at risk of COVID-19 were over 65, and perhaps their deaths were less shocking. In contrast, younger people felt relatively safe. In 1918 it was people in the prime of their life who were dying, as well as their children. This made people feel more vulnerable.

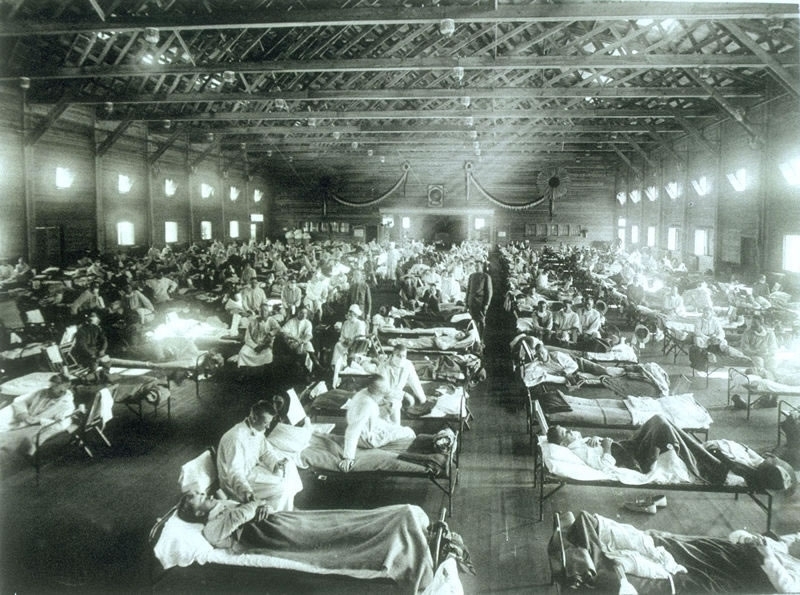

Today, people typically die in the hospital. In 1918, if you lived in a rural area -as did most of the population- a trip to the hospital would take time and might not be easy. More people were cared for –and died– at home. I think that this meant that people saw the results of outbreak much more directly. Today, the ill vanish into hospitals. Their suffering leaves nurses and doctors traumatized, but isn’t visible in the same way that the 1918 pandemic was, when family members and neighbors would see the bodies taken out the front door.

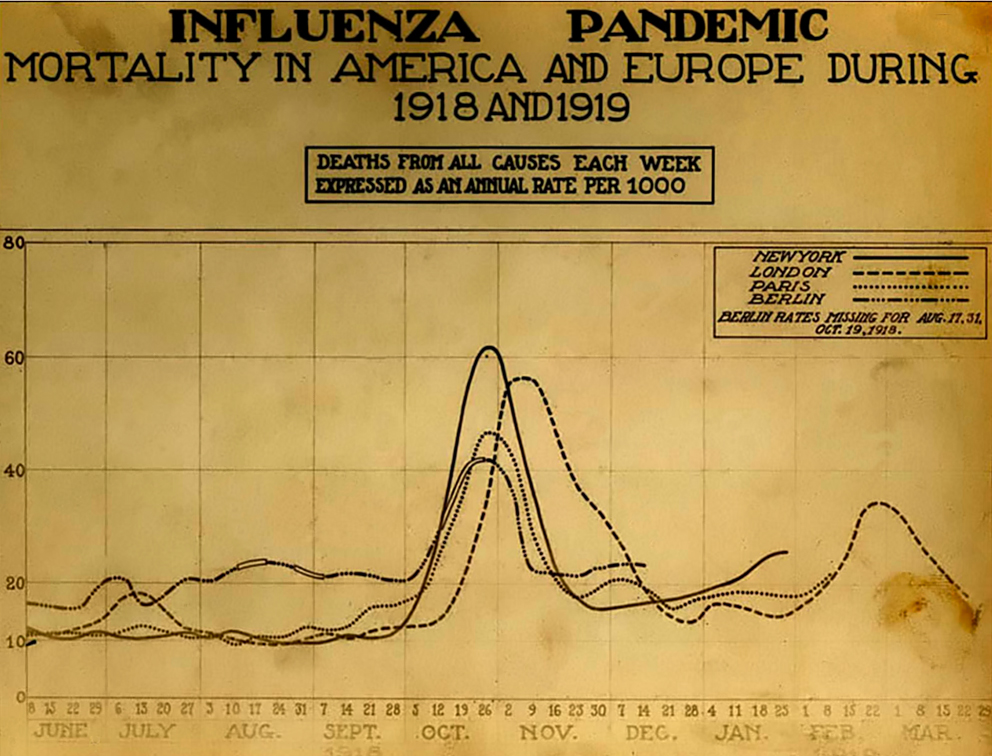

There were three distinct waves to the 1918 influenza pandemic. But the fall 1918 wave had a much higher peak in the death rate. Of course, the spring 1918 influenza outbreak was terrible in some places such as the military camps in Kansas. But by November 1918 the number of deaths was so crushing that denial was no longer an option in many communities. People were too busy taking care of their neighbors; everyone could watch the gravediggers. COVID-19 has been more spread out, which has changed how people have talked about it.

The US population was much smaller in 1918 than now, at just over 103 million people, versus 328.2 million. So although the total numbers of deaths are similar, the death rate was roughly three times higher a century ago. People saw much more death during the 1918 pandemic.

I also wonder if people didn’t have a different attitude towards medicine. The 1918 pandemic took place before most childhood vaccines, antibiotics, and modern therapies. People had more limited expectations for what a doctor might do. Now, it might be that many people expect that if they go to the hospital they will be saved, because they have often seen sick family members or friends healed in a hospital. I can’t prove this, but I suspect some COVID-19 patients are shocked when they find out that they will die. In 1918, people respected and valued doctors, but the life expectancy for men was 36.6 years, and 42.2 for women. People didn’t feel as invulnerable -and didn’t assume that the hospital would save them- because they were more familiar with death. In 1917 -the year before the pandemic- the second most common cause of death in the US was pneumonia and influenza.

Of course, in 1918 people relied heavily on newspapers and the government for information, whereas now people turn to social media. But I think that people were more familiar with infectious illness in 1918, and experienced the pandemic in a different way than with COVID-19. This difference perhaps helps to explain why in many states people seem to be much less afraid of COVID-19 than their great-grandparents were during the 1918 pandemic.

Shawn Smallman